Erika Sprey

December 2023

I always tend to sense injustice in my gut first. Nestling itself in the intricate folds of what writers Rupa Marya and Raj Patel call the enchanted forest within, I feel it as an irritant at first, causing unease, confusion. I tend to gaslight myself: is it real what I’m perceiving? Is it injustice that I am sensing? Having been raised for large parts of my life in a Western knowledge system, which privileges mind over matter as two separate entities, and suffering from an autoimmune disease that affects the gut, it has been an ongoing process to unlearn my tendency to ignore, mistrust, and misinterpret my gut feelings, and learn how to let them fully sink in and let them be my merciful guide. My gut guides me now when I walk into the woods, towards the pain, because at the end of the day, I know my body will very acutely, precisely, and inevitably manifest what my mind can’t or doesn’t want to assume. My gut calls me into the woods because injustices suffered, when left unaddressed and untreated at an early stage, will grow into a malignant, predatory pathogen, inflaming, draining, and collapsing systems from within.

Coming from a family in art, activism, and law, it has been vital for me to deconstruct justice as more than a distant, mental, aspirational concept - a capacity of the supposedly rational, moral mind that seeks, for instance, a just distribution of goods, opportunities, and resources across society. Happily, during the pandemic, a growing body of literature and practices has started to emerge that approach justice as a primarily embodied phenomenon that affects all layers of the body: physical, social, political, and even cosmological, all interconnected in fractal-like configurations. Justice is able to traverse personal and collective sympathetic nervous systems, triggering societal autoimmune responses, settling within connective tissues, and becoming an 'indigestible' entity within a cosmology when it receives no reckoning, reparation, or redemption.

Injustice, in other words, causes a form of inflammation that does not generate the usual beneficial healing response that we would typically expect—strengthening, for instance, immune systems and cell membranes, in service of the diversity of the enchanted forest. Injustice is another kind of beast. It behaves, in my view, as what Tyson Yunkaporta would call a curse: ‘The curse is a deception made real—either an outright lie or a true law or pattern applied where it doesn’t belong. It is like a computer virus, a sneaky line of code that ends up crashing the whole system’ (my italics). It may also behave itself as what Michel Serres calls a parasite: an interrupting ‘noise, like the static in a system or interference on a channel, thwarting every attempt at smooth, efficient communication’, and an agent ‘who has the last word, who produces disorder and who generates a different order’. No system is without its flaws, losses, errors, accidents, and excesses; the parasite, however, exploits these, feeds on them, while infesting the bodies with one-way, linear, irreversible relations.

Injustice, whether conceived as a cursing parasite or a parasitical curse, involves the deliberate derailment and exploitation of blind spots within systems, effectively making deceptions 'real'. This undermines the potential for a 'return to oneself', obstructing any access to reckoning, reparation, redemption, or, in other words, deep medicine.

Both 'parasite' and 'curse' are very violent and charged words: the former has been historically used to dehumanize people and legitimize atrocities, while the latter instills the belief that we are destined to remain trapped in these insidious and deeply harmful linguistic constructs and that there is no ‘outside’ or viable alternative than submitting and following through the same destructive course. I also want acknowledge the particularly malignant role the word parasite has played in the long history of antisemitism and the Holocaust, and how the same animal rhetoric is continued to be used to characterize and insidiously dehumanize certain countries and peoples. (1) In tandem, parasite and curse are able to perpetuate endlessly repeating patterns of re-traumatization along a singular, linear path that goes from bad to even worse. We see these beasts again reappear in the horrific genocide in Gaza that we are globally witnessing and which is reconfiguring the world it in ways that we cannot yet comprehend. What will emerge from this new cycle of intergenerational, continuous and enduring wounding by rabid settler colonialist violence?

I imagine all the livestreamed injustices that we ingest every day nestling in our collective gut as intractable, indigestible matter, inflaming all interconnected bodies - physical, social, political and even cosmological – that were already made sick by the enduring histories of oppression and colonialization.

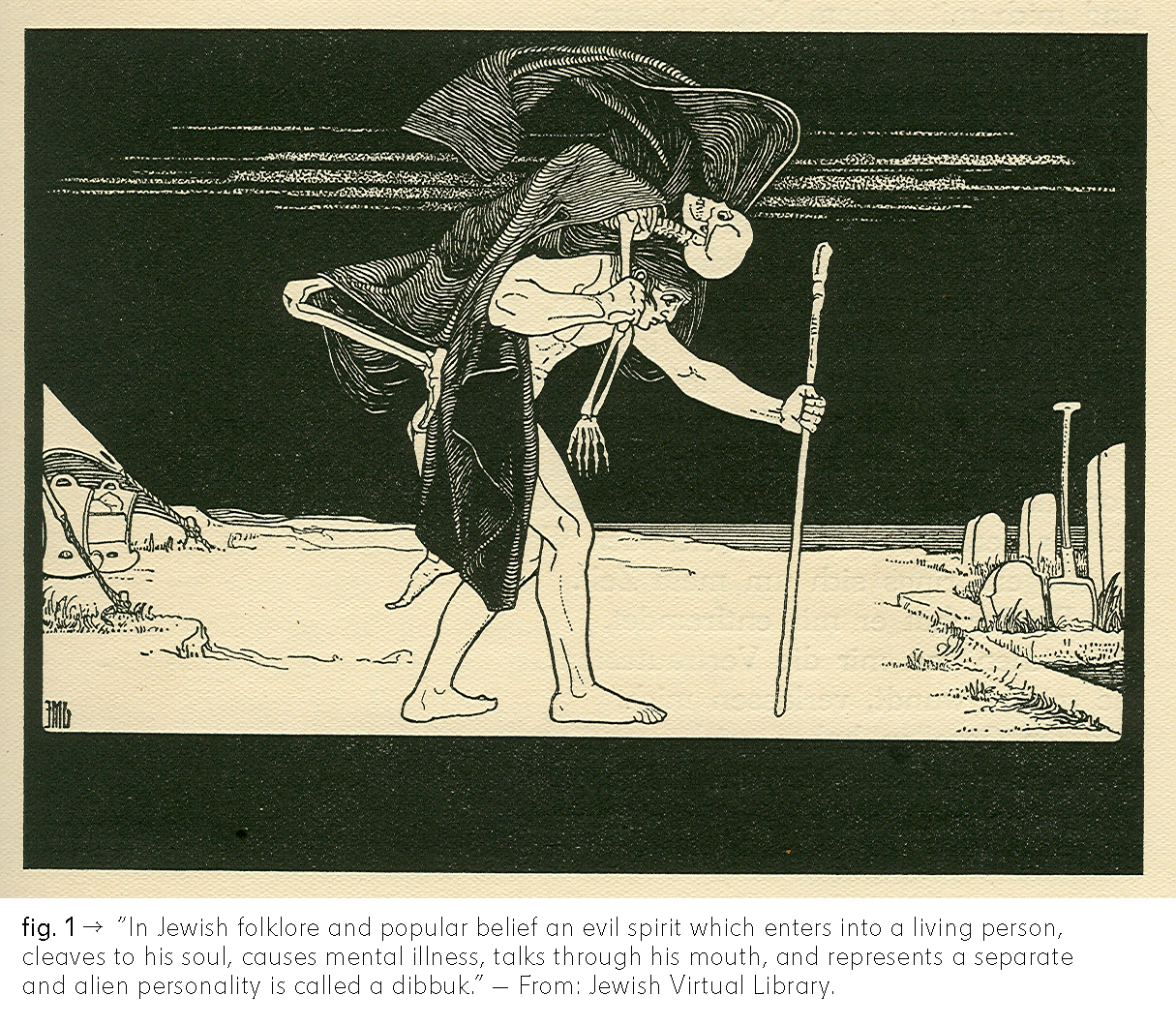

I imagine all this indigestible stuff we see unfold on a daily base to coalesce and animate what I see as a new kind of dybbuk, an amalgamation of all the souls that were unjustly murdered in Gaza latching onto all political, social and actual bodies that either look away, actively facilitate or execute the killing. Of course, these murdered souls are not literally clinging to living persons, as the old Jewish folktale would have it, and certainly not to become an “evil” revengeful spirit—that would add insult to unspeakable injury and the immense grief in the make. I rather rely on the ancient folk wisdom that every that has found a premature, unnatural and/or violent death, and is not put to rest well, will continue to wander and haunt people and the collective imaginary until they are fully grieved and redeemed. [fig. 1]

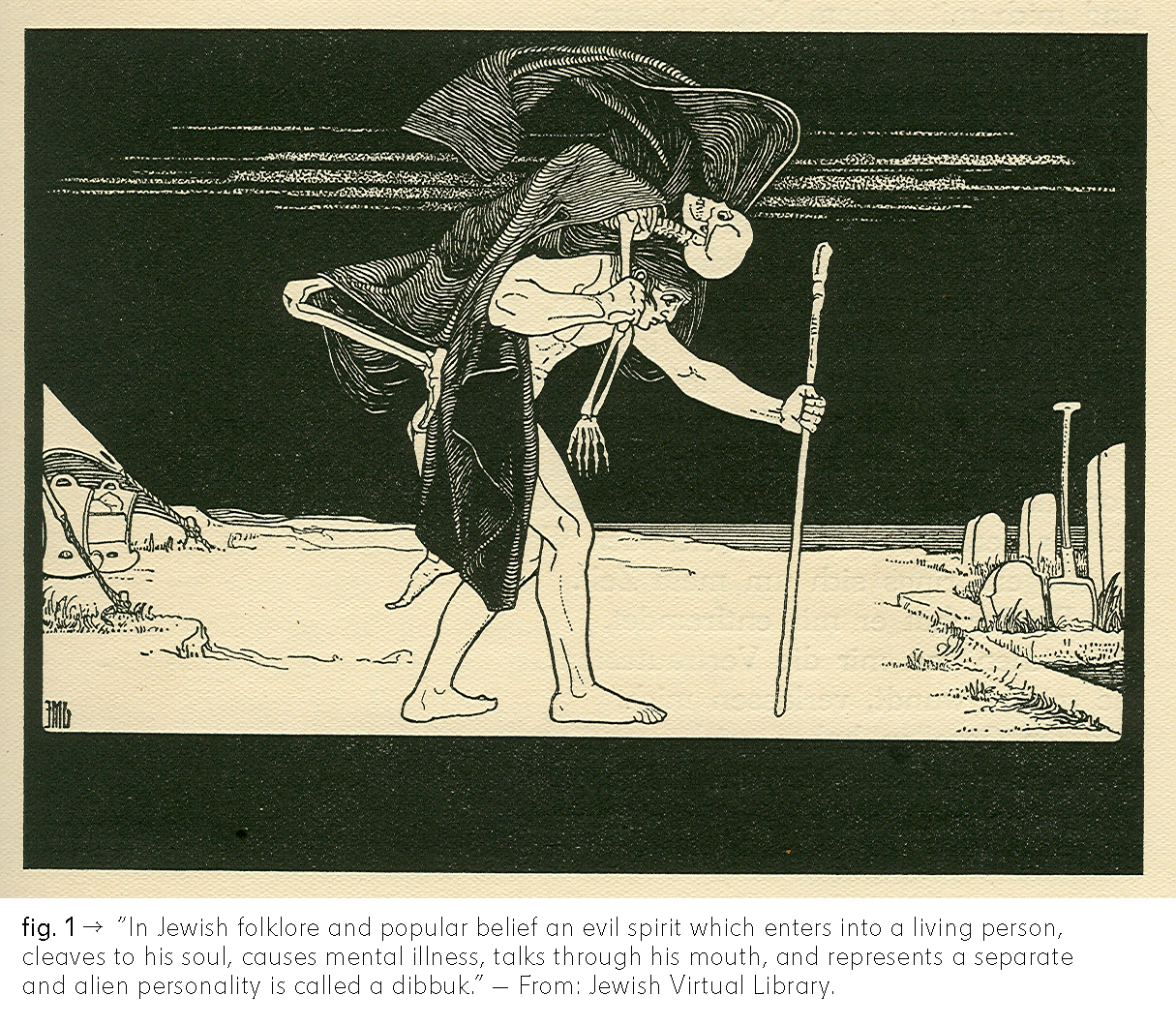

I also imagine all this indigestible stuff passing through the hands of Janus, the Roman god of beginning and endings (and specifically of conflict), dualisms, doors, passageways, and transitions. With its angry face, it causes (t)issues to swell and fester, while with its fearful face, it freezes and transfixes them. Janus will obstruct any passage until every facet of injustice is thoroughly contemplated, confronted, and faced. Facing: acknowledging the irreducible, otherness of the other in the face of the other: you are another myself.

Clearly, facing all the faces of Janus demands a willingness to "lose face," and many may be tempted to look away. The mere prospect of experiencing shame and guilt in the presence of the victim is sufficient to cause some to crumble into ashes. That is why so many will attempt to corral this ‘problem of injustice’ with legalistic frameworks, reductive methods, and pseudo-solutions while appealing to authority, (capital) realism, and/or an insidious ‘right to self defense’. Meanwhile, Janus, continues to dismantle obsolete frames, rendering the (t)issues underneath untreatable, incuratable, indigestible. [fig. 2]

Miranda Fricker eloquently introduces the two faces of epistemic injustice on the first page of her insightful book: the testimonial kind arises when the speaker is disregarded and/or taken less seriously because of implicit and explicit prejudices surrounding a person's identity (e.g. homophobia, xenophobia, misogyny, ableism). The hermeneutical kind is more elusive and perhaps even more fundamental, as it’s about who gets to decide on and controls the rules of the language game, that is: the conceptual frameworks that allows one to recognize and articulate the suffered injustice in the first place. After all, the best prison is the one that is not perceived as a prison at all. But no matter how much these language games are able to enclose one’s sense of reality, bodies remember, and indigestion will continue to inflame and fester, albeit in more subterranean ways. Lastly, Janus and the dybbuk pay tribute to the “moral residue” as defined in biomedical ethics: the feelings of anxiety that come from an integrity-compromising situation that finds no satisfactory resolution. It is conceived as an occupational hazard for those working closely with life and death and often face impossible choices between several inescapable evils. This residue follows the logic, and creates the same kind of stress, of what system thinkers Paul Watzlawick and Gregory Bateson have described as the double bind: when one is caught in a ‘closed system’ in which one receives two or more mutually conflicting messages, one will always find themselves on the failing, losing side. Damned if you do (or have done), damned if you don’t (have done), and what’s more, there will be no language or framework to meta-communicate what one is going through, let alone call this ‘epistemic injustice’.

The dream space is no stranger to epistemic injustice, as dreams have often been diminished in the West as irrelevant, irrational, and mere background noise of dominant day-consciousness. They are not taken seriously as a form of knowledge with potential social and political significance in the supposedly real world. Mystical, premonitory 'big dreams' that could influence the fate of an individual or collective have been relegated to quaint, symbolic, metaphorical 'stories' from the past. Ancient Greeks and later the European Enlightenment prioritized truth-seeking and myth-busting through logos and ratio, relegating dreams to mere fiction, figments of imagination unfolding in our nightly internal theater. The dream world became the shadow world, a realm beyond law and morality—irrational, unruly, and lascivious—and thus deemed dangerous and to be repressed at all costs to keep the wheels of the capitalist machinery spinning.

Later, dreams did receive some form of appreciation at the hands of psychoanalysis and neuroscience, which deemed them a 'useful' function of both brain and psyche. Sigmund Freud notably asserted that the interpretation of dreams is 'the royal road to the unconscious,' emphasizing that dreams are constructed from residues of daytime experience. This perspective resonates with certain strands of neuroscience conceiving dreaming as akin to a "second gut," digesting accumulated information throughout the day. The brain detoxifies, integrates daytime experiences, promotes deep learning, and imprints memories in the neural network during dreaming.

The question remains: what happens to injustices that our system can’t process? How do moral residues haunt our dreams? What becomes of our collective bile? While psychology and neuroscience have shown that dreaming helps to process individual trauma to some extent, they offer little to no answers for collective traumatization—especially the kind that persists, defying any baseline of non-traumatization.

Our gut calls us into a forest reminiscent of the one inhabited by the Astheans, the indigenous people of planet Asthe depicted in Ursula Le Guin's renowned novel, "The Word for World is Forest." Dreaming holds profound significance for the Astheans, far from being the fringe phenomenon it is in our disenchanted world; it is integral to their communal life and well-being, allowing them to receive ancestral guidance, communicate with the more-than-human world, navigate conflict and violence, and ensure the preservation of their culture. Collective dreaming serves as their method of processing collective experiences and emotions, including the trauma inflicted upon their society by invading human colonizers, as well as grief, conflict, and the emergence of new realities amidst adversity.

And sometimes a new ‘god’ enters the stage that radically changes the way this collective dream unfolds:

“Sometimes a god comes,” Selver said. “He brings a new way to do a thing, or a new thing to be done. A new kind of singing, or a new kind of death. He brings this across the bridge between the dream-time and the world-time. When he has done this, it is done. You cannot take things that exist in the world and try to drive them back into the dream, to hold them inside the dream with walls and pretenses. That is insanity. What is, is. There is no use pretending, now, that we do not know how to kill one another.”

With the genocide in Gaza presently unfolding before our eyes in world-time, a new god has also emerged within our collective dream-time, releasing new demons to haunt us for the next generations to come. It would indeed be insanity to deny that we are not witnessing a new way of killing and weaponizating trauma, further exacerbating an already highly inflamed and inflammable situation. The advent of this new god, like any event that confronts us with our capacity for doing evil, will fundamentally change the way we see ourselves in all our (in)inhumanity, hopefully prompting a new cycle of deep reckoning. It will nestle itself within the folds of our disenchanted forest, awaiting the moment when things fall apart and the center can no longer hold, eviscerating even further the world as we know it.

.....

An example of this is found in the astonishing column of Thomas L. Friedman in the New York Times of 2 February 2024. ‘Iran is to geopolitics what a recently discovered species of parasitoid wasp is to nature. What does this parasitoid wasp do? According to Science Daily, the wasp “injects its eggs into live caterpillars, and the baby wasp larvae slowly eat the caterpillar from the inside out, bursting out once they have eaten their fill. Is there a better description of Lebanon, Yemen, Syria and Iraq today? They are the caterpillars. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps is the wasp. The Houthis, Hezbollah, Hamas and Kataib Hezbollah are the eggs that hatch inside the host — Lebanon, Yemen, Syria and Iraq — and eat it from the inside out. We have no counterstrategy that safely and efficiently kills the wasp without setting fire to the whole jungle.’ https://www.nytimes.com/live/2024/01/30/opinion/thepoint#friedman-middle-east-animals

This piece was commissioned by Home Cinema as a text contribution to their closing event of 2023: The Deep: Last Dream of the Year.